Back in the now-far-off year of 2013, Elon Musk announced his proposal for a novel "fifth mode of transport." A fully autonomous, ultra-high-speed transportation system that he himself christened the hyperloop. A pod-based system that wisps back and forth through a series of tubes between cities nearly as fast, if not quicker, than traveling by air. Since then, many have tried to bring this idea to fruition, including the Virgin Group, but all of them have failed.

But over 150 years ago, under the soil of Lower Manhattan, one man's vision nearly turned the New York City Subway into something that looks an awful lot like an 1800s design for a hyperloop. Elon Reeve Musk, say hello to Alfred Ely Beach. If Mr. Musk did have access to the time machine he surely wishes he had, he'd have gone back to sue the pants of Mr. Beach for stealing his idea.

Luckily for Elon, there was already a cartoonishly evil Gilded Age business tycoon doing the job for him. But that's the conclusion of the Beach Pneumatic Transit system, not its beginning. To understand the full story, we need to understand what New York City was like in the very early days after the American Civil War. In the same way that World War II was defined by piston-engine fighters or how the Vietnam War was defined by helicopters, the US Civil War was defined by steam locomotives and railroads in many respects.

The Association of American Railroads details that the Union sported roughly twice the mileage or railway across its territory than that of the Confederacy, nearly 20,000 miles of track compared to just 9,000 down south. Without a side-diatribe that derails the story (see what I did there?), Union Army tactical and strategic doctrine specifically targeted the scarce rail infrastructure the Confederacy did have on hand as it made its way into enemy territory. In some cases, locomotives and rail cars using the same track gauge were often stolen by either side and pushed into enemy service, sometimes multiple times over the course of the war.

During General William Tecumseh Sherman's iconic 1864 March to the Sea campaign through Georgia, Union Soldiers famously treaded Confederate rail infrastructure with all the hostility of Hades reincarnated as they retreated up north. By the time General Lee walked up to Appomattox Courthouse in 1865, little was left of Southern US rail infrastructure. However, rail infrastructure was largely untouched in former Union-aligned states, notably New York and Pennsylvania.

With that in mind, the Reconstruction Era would prove to be a transformative period for troops returning home in a handful of former Union cities. Future powerhouse cities like New York and Chicago had already flirted with complex rail networks for freight and passenger service before the first shots of the Civil War were fired. One Long Island Railroad tunnel even ran underneath Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn as far back as 1844, albeit without any subway stop service as you'd expect.

New York City's first commuter/freight rail service to enter operation was the New York and Harlem Railroad, whose first set of tracks were laid from the Bowery up to 14th Street near the site of what is today Union Square via Prince Street and the SoHo neighborhood in 1832. By the end of the Civil War, the NY&H Railroad had expanded all the way north to 42nd Street, at the site of Grand Central Depot, which also operated by the titanic New York Central Railroad, itself a conglomerate of several smaller Railroads from across New York State and further afield. Today, this is the site of the iconic Grand Central Terminal building that houses the terminus for the modern Metro North and Long Island Railroads.

But what many of New York City's elite desired was a subterranean commuter rail network that could rival the one that'd just commenced operation across the ocean in London only a handful of years earlier. The very earliest days of the London Underground, or the Metropolitan Railway as it was known back then, were marked by typical steam locomotives carrying oil lamp-illuminated wooden railcars through freshly dug, smoke-filled tunnels built using tried and true cut and cover methods to carve their way through the soil between the neighborhoods of Paddington and Farrington.

But as New York's elite looked across the pond in admiration of the work done in London, Alfred E. Beach envisioned an underground mass transit system that didn't belch toxic smoke in the faces of its riders as they made their way to work in the morning. In fact, Beach's idea didn't involve any traditional locomotives at all. Born in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1826 as the son of the esteemed publisher and owner of the New York Sun Newspaper Moses Yale Beach, it can be argued that the young Beach was set up for success in the field of science from birth.

Yes, the Yale in his father's middle name refers to the family that founded the eponymous University. Combined with his father's prowess as a publisher and a boyhood fascination with inventions, Alfred Beach's post-war work under his father's firm paid dividends as it purchased the intellectual property rights for the new and quickly-rising magazine Scientific American from the painter and inventor Rufus Porter. With the help of their colleague Orson Desaix Munn, the Beach family had a firecracker of an IP under their belt. Scientific American would soon immerse Alfred Beach into a world of research, engineering, and academia that'd train his mind to think outside the box.

Beach spent the years post-1846 attracting offers from inventors who hoped to use the magazine's public influence to obtain patent opportunities through Scientific American's sister company, Munn & Co, at 37 Park Row in Lower Manhattan, near City Hall and the modern site of the World Trade Center complex. One of those men who strutted into Alfred Beach's office happened to be Mr. Thomas Alva Edison. The invention he had in hand? That'd be the phonograph. As it happens, Edison was a boyhood fan of Scientific American.

Through his patent brokerage business, Alfred Beach would soon become the Reconstruction Era equivalent of a modern New York baller. Now, sufficiently independently wealthy, all that time mingling and fraternizing with some of the smartest folks on Planet Earth was about to pay off in a big way. By the end of the Civil War, Beech had an impetus to design his pod-based pneumatic underground transit system.

Above ground, the streets of Manhattan were a totally sorry display. Roads and streets were routinely so full of horse manure that the stench emanated as far away as Brooklyn and Staten Island. Small wonder that Brooklyn didn't integrate into New York City proper until 1898; the smell alone must've been a big enough deterrent. All the while, the almost laughably unsanitary conditions were legitimately making Manhattanites ill with its filth and waste. To make matters worse, street-level freight and passenger trains that trundled across the streets of Manhattan alongside pedestrians created gruesome results that don't need graphic detail.

With New Yorkers splattering themselves into paste after impacting oncoming locomotives by the dozens, Alfred Beach had the perfect opportunity to expand his pneumatic mass transit concept into something he could pitch to city officials for a shot at public subsidies. Beach even designed a novel ground-carving and support structure device that simultaneously dug a tunnel and kept it standing before there was a chance for engineers to make the tunnel structurally sound long-term. These devices are known as tunneling shields and are still used to this day.

The first of these devices was invented by the French Marc Isambard Brunel, the father of the man who was seen as the inventor of all inventors of his day, the Anglo-French heavyweight Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Beach's plan was to take Brunel's idea and modify it from a rectangular apparatus suitable for normal locomotives and railcars into a system fit to accommodate cylindrical wooden passenger pods. It's here where comparisons between Beach's pneumatic transit system idea for New York City and Elon Musk's modern Hyperloop concept become increasingly apparent.

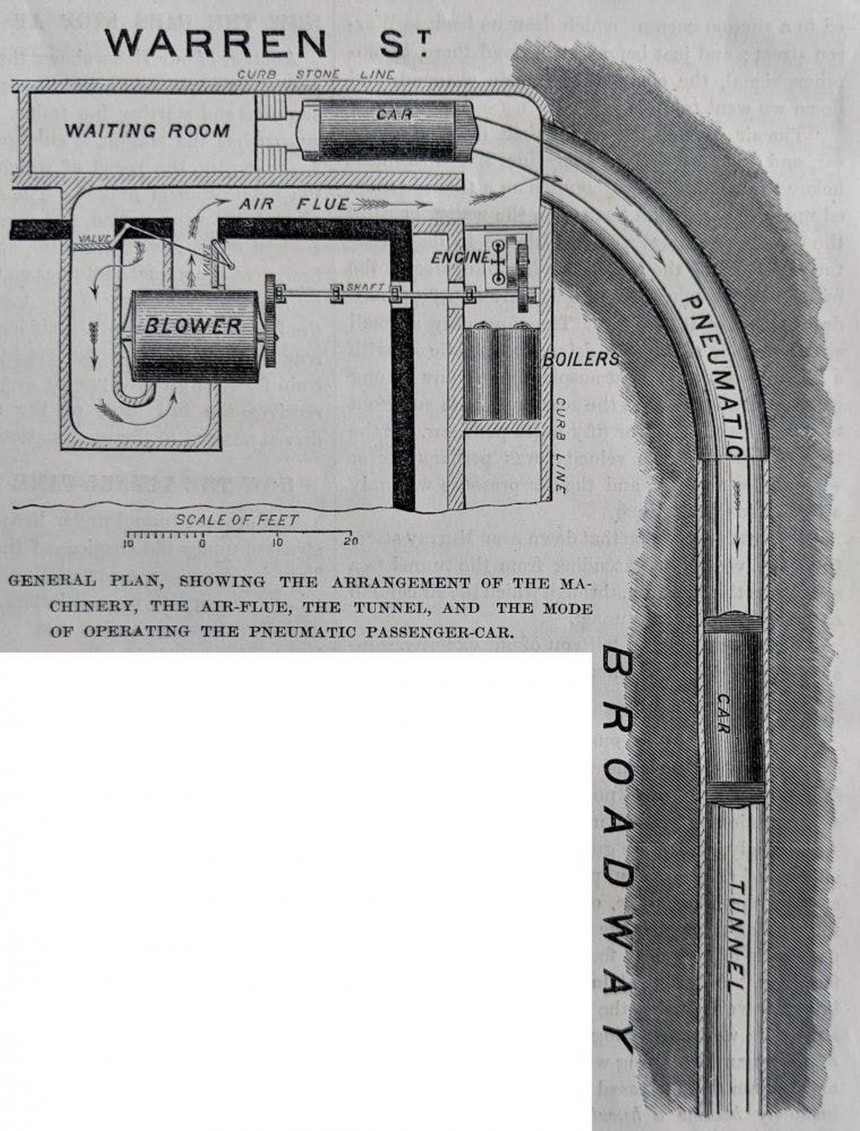

Like Hyperloop, the Beach Pneumatic propelled individual a barrel-shaped pod across a cylindrical pathway using the differentiating pressure both in front of and behind the pod to propel it down a set of specially-built rails that almost resemble modern tram lines than typical railway ties and tracks. Where Elon Musk touted the hyperloop as sharing battery and motor technology with roadgoing Tesla EVs (allegedly), Beach's first prototype model used a roughly 100-horsepower fan to provide enough differential pressure in the right direction to propel the pod forward.

Granted, the engineering particulars of Musk's concept for Hyperloop aren't exactly the same as the Beach Pneumatic Transit system. But at least from a purely aesthetic perspective, the parallels are indeed profound. Alfred Beach presented his first scale model for a pneumatic pod transit system at the American Institute Fair at New York's 14th Street Armory in 1867. Though little more than a wooden suspended tube and a simple mockup transit pod, the Beach Pneumatic Transit system arguably looked even more like a steampunk Hyperloop in concept form than it did in practice.

In the same spirit as pneumatic mail tubes popping up across cosmopolitan cities like London, the basis of Beach's design did attract attention from investors. In 1869, the Beach Pneumatic Transit Company was formed with the intent of finding a spot to build the first stretch of their new mass transit line. Beach's first couple of attempts to secure a permit with NYC authorities were denied, but legend said he just started building the tunnels in secret, using the cover of building a London-style pneumatic mail tube system along Broadway in Lower Manhattan instead to keep the powers that be off his rear-end; that cheeky man him.

Starting directly across from NYC City Hall at the intersection of Warren Street and Broadway, it took just 58 days for Beach's tunneling shields to make mince meat of the subterranean soil around 20 feet or so underground, effectively placed smack-dab in one of the basement levels of the structure above, the Rogers Peet Building. White brick adorning the interior station walls located underneath Warren Street, complete with a bronze statue at the entrance to the tunnel reminiscent of Greek and Roman design cues, all made the station a very pleasant place to wait. The trackside goldfish pond and grand piano must've been a treat as well.

Its tram-like rail path was built with an extremely prominent curve that initially ran east using steam power provided from a boiler and blower room near the terminal towards Broadway. From there, it would hook south down Broadway roughly 300 feet or 90 meters towards the opposite end of Murray Street before returning back to the single station on the route. The total distance covered was about a block and some change. The pod itself was a marvelous piece of engineering in its own right. With plush couches to sit on and lit inside by zirconia lamps, the extra artificial light accented the ornate woodwork inside the pod as it made its transit through the basement of what was then Devlin's Clothing Store.

Though undoubtedly more of a novelty for city folks to gawk at than a functional subway, the resulting fanfare when Beach's Pneumatic Transit line opened on February 26th, 1870, couldn't be denied. Hundreds of thousands flocked to Lower Manhattan to ride a transit system in the making unlike any other in the world. With only one car and one station total, the economy of scale, when applied to an entire multi-line subway system, would've made Alfred E. Beach rich beyond most people's wildest imaginations if it expanded. By all metrics, it looked like that's the direction the Beach Pneumatic Transit system was headed. So the story goes, plans even called for the system to expand past New York Central Railroad Territory on 42nd Street and as far north as the southern tip of Central Park near the 59th Street-Columbus Circle station.

At least, that's what probably would've happened had the real supervillain of the story not meddled in the affair. Biases aside, if Alfred Beach is the Elon Musk of this equation, then William M. "Boss" Tweed is Jeff Bezos. An astonishingly wealthy and equally corrupt NYC landowner, politician, bank mogul, and businessman with substantial financial capital tied to New York State's traditional above-ground elevated rail systems, Beach's Pneumatic Transit System was like SpaceX and Tweed's board membership of the Third Avenue Railway Company was his Blue Origin.

In short, Boss Tweed wanted Beach's proto-hyperloop idea for the New York City Subway thrown in the trash in favor of projects he was invested in. As it turned out, Boss Tweed was personally profiting on every single above-ground passenger train that made its way into Manhattan. He had plans to effectively take the modern paradigm of the Subway and bring it above ground if given his way. With Boss Tweed's increasingly greased palms perpetually interfering with attempts to expand New York's Pneumatic Transit line, a ridership of 400,000 people during its first year at 25 cents a pop (almost $6 in 2024 money) wasn't enough to save the line from archetypal NYC corruption.

Turns out, Boss Tweed was a leading member of NYC's Tammany Hall elite who initially denied Beach's proposal. Suffice it to say, Tweed went full nuclear with rage when he learned he'd been tricked into letting Beach build a "mail tube system" right under his nose that became a rival to his elevated rail ambitions. But believe it or not, it wasn't Tweed who tombstoned the Beach Pneumatic Subway. He wound up (for once in one of these corruption stories) getting what was coming to him after being convicted of stealing New York taxpayer money as a member of the State Senate. He died in Lower Manhattan's Ludlow Street Jail in 1878, but not before a failed escape attempt.

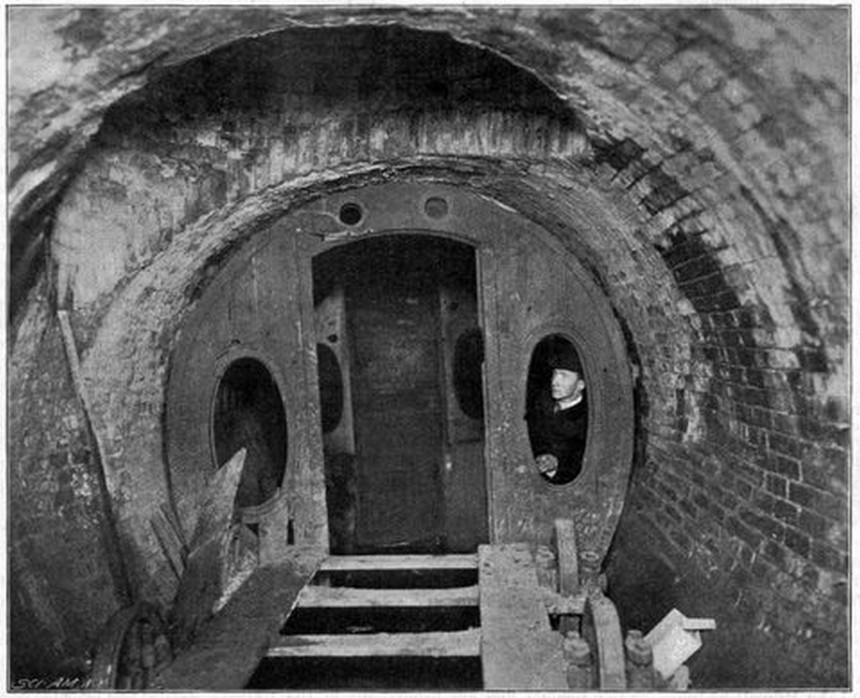

Instead, one of the largest pre-1929 stock market crashes in the history of the New York Stock Exchange meant that by 1873, funding to expand Beach's Pneumatic Transit network, by which time he had the green light to go ahead, had dried up. By the end of the year, the line was completely abandoned, and the building above was lost to fire in 1898, two years after Beach himself died of Pneumonia, aged 69. After the fire, the remains of the tunnel were photographed, with some posing inside the derelict passenger pod before being boarded up and sealed, not to be seen again until 1912.

It was here where construction workers for the Degnon Contracting Company employed to extend the modern-day BMT Broadway Line, consisting of the N, Q, R, and W trains nowadays, happened upon Beach's tunnel. Allegedly, the original passenger pod and tunneling shield were still inside. If you thought workers proceeded to preserve these quite literally priceless pieces of NYC transit history, you'd be dead wrong. They demolished just about every piece of infrastructure ever built at the site to make way for more BMT Broadway Line infrastructure. So that begs the question, is there anything still around from this Beach Pneumatic Transit system today?

Well, the answer can only be described as *shrug*. In truth, it's pretty up in the air, with speculation running rampant in online forums like Reddit about what remains. As recently as late March 2023, a YouTuber going by kbnyc traveled to the building built after the 1898 fire and ventured three floors down to its sub-basement to look for clues of Subway's past. Indeed, the plaque in the front lobby of 258 Broadway, now known as City Hall Tower, at the corner of Warren Street commemorates the historic transit system hiding underneath. Today, the basement is full of bicycles used by the tenants who live upstairs, as well as the occasional roughly pug-sized New York mutant super rat.

But as this adventurous YouTuber walks further across the basement floor, a very familiar yet dilapidated set of white bricks with dingy, faded paint appears. It also happens that the bricks are arranged in an equally identifiable curve arrangement. With that in mind, it's at least a safe bet, but not a sure thing, that we're looking at all that remains of New York City's true first underground transit network. On the other end of that wall supposedly sits infrastructure for the local BMT R train between Bay Ridge–95th Street in Brooklyn and looping through Manhattan, usually to Forest Hills–71st Avenue station in Queens.

So far as we can tell, the basement resides on the site of the former station waiting area, where people would descend a flight of stairs to board their pod. Moving to the next room, which has to be propped with a piece of wood, leads to the only staircase in this portion of the sub-basement, after which appears an array of ancient-looking coal furnace piping that might indicate that it's the former location of either the blower or boiler room. In addition, he locates a semi-separate section of the room that might've served as the on-site bathroom.

Further down the hall sits a set of what looks like electricity meters with patents dating to 1888. It's certainly older than the building above, but not quite 1870s old. A few steps further reveal what could be the old engine room, but then again, so much reconstruction has been done since the 1870s that verifying any of this is next to impossible without the help of experts. But to think that the remnants of such a historical footnote in New York City's history might be lingering, chilling out underneath a typical Manhattan apartment building, right beneath everyone's noses, is an exhilarating one. Will it ever be matched and surpassed by a modern pneumatic hyperloop one day? The answer remains very much up in the air, especially as of the last 12 months.

To think such an unappreciated icon exists a mere stone's throw away from both the current Brooklyn Bridge–City Hall station and the long-abandoned crown jewel of the modern New York Subway, old City Hall Station, makes this part of Lower Manhattan effectively like sacred grounds for fans of metro transit around the world. But speaking of Old City Hall, that's a story for another time; be sure to stay tuned for that.

Luckily for Elon, there was already a cartoonishly evil Gilded Age business tycoon doing the job for him. But that's the conclusion of the Beach Pneumatic Transit system, not its beginning. To understand the full story, we need to understand what New York City was like in the very early days after the American Civil War. In the same way that World War II was defined by piston-engine fighters or how the Vietnam War was defined by helicopters, the US Civil War was defined by steam locomotives and railroads in many respects.

The Association of American Railroads details that the Union sported roughly twice the mileage or railway across its territory than that of the Confederacy, nearly 20,000 miles of track compared to just 9,000 down south. Without a side-diatribe that derails the story (see what I did there?), Union Army tactical and strategic doctrine specifically targeted the scarce rail infrastructure the Confederacy did have on hand as it made its way into enemy territory. In some cases, locomotives and rail cars using the same track gauge were often stolen by either side and pushed into enemy service, sometimes multiple times over the course of the war.

During General William Tecumseh Sherman's iconic 1864 March to the Sea campaign through Georgia, Union Soldiers famously treaded Confederate rail infrastructure with all the hostility of Hades reincarnated as they retreated up north. By the time General Lee walked up to Appomattox Courthouse in 1865, little was left of Southern US rail infrastructure. However, rail infrastructure was largely untouched in former Union-aligned states, notably New York and Pennsylvania.

New York City's first commuter/freight rail service to enter operation was the New York and Harlem Railroad, whose first set of tracks were laid from the Bowery up to 14th Street near the site of what is today Union Square via Prince Street and the SoHo neighborhood in 1832. By the end of the Civil War, the NY&H Railroad had expanded all the way north to 42nd Street, at the site of Grand Central Depot, which also operated by the titanic New York Central Railroad, itself a conglomerate of several smaller Railroads from across New York State and further afield. Today, this is the site of the iconic Grand Central Terminal building that houses the terminus for the modern Metro North and Long Island Railroads.

But what many of New York City's elite desired was a subterranean commuter rail network that could rival the one that'd just commenced operation across the ocean in London only a handful of years earlier. The very earliest days of the London Underground, or the Metropolitan Railway as it was known back then, were marked by typical steam locomotives carrying oil lamp-illuminated wooden railcars through freshly dug, smoke-filled tunnels built using tried and true cut and cover methods to carve their way through the soil between the neighborhoods of Paddington and Farrington.

But as New York's elite looked across the pond in admiration of the work done in London, Alfred E. Beach envisioned an underground mass transit system that didn't belch toxic smoke in the faces of its riders as they made their way to work in the morning. In fact, Beach's idea didn't involve any traditional locomotives at all. Born in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1826 as the son of the esteemed publisher and owner of the New York Sun Newspaper Moses Yale Beach, it can be argued that the young Beach was set up for success in the field of science from birth.

Beach spent the years post-1846 attracting offers from inventors who hoped to use the magazine's public influence to obtain patent opportunities through Scientific American's sister company, Munn & Co, at 37 Park Row in Lower Manhattan, near City Hall and the modern site of the World Trade Center complex. One of those men who strutted into Alfred Beach's office happened to be Mr. Thomas Alva Edison. The invention he had in hand? That'd be the phonograph. As it happens, Edison was a boyhood fan of Scientific American.

Through his patent brokerage business, Alfred Beach would soon become the Reconstruction Era equivalent of a modern New York baller. Now, sufficiently independently wealthy, all that time mingling and fraternizing with some of the smartest folks on Planet Earth was about to pay off in a big way. By the end of the Civil War, Beech had an impetus to design his pod-based pneumatic underground transit system.

Above ground, the streets of Manhattan were a totally sorry display. Roads and streets were routinely so full of horse manure that the stench emanated as far away as Brooklyn and Staten Island. Small wonder that Brooklyn didn't integrate into New York City proper until 1898; the smell alone must've been a big enough deterrent. All the while, the almost laughably unsanitary conditions were legitimately making Manhattanites ill with its filth and waste. To make matters worse, street-level freight and passenger trains that trundled across the streets of Manhattan alongside pedestrians created gruesome results that don't need graphic detail.

The first of these devices was invented by the French Marc Isambard Brunel, the father of the man who was seen as the inventor of all inventors of his day, the Anglo-French heavyweight Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Beach's plan was to take Brunel's idea and modify it from a rectangular apparatus suitable for normal locomotives and railcars into a system fit to accommodate cylindrical wooden passenger pods. It's here where comparisons between Beach's pneumatic transit system idea for New York City and Elon Musk's modern Hyperloop concept become increasingly apparent.

Like Hyperloop, the Beach Pneumatic propelled individual a barrel-shaped pod across a cylindrical pathway using the differentiating pressure both in front of and behind the pod to propel it down a set of specially-built rails that almost resemble modern tram lines than typical railway ties and tracks. Where Elon Musk touted the hyperloop as sharing battery and motor technology with roadgoing Tesla EVs (allegedly), Beach's first prototype model used a roughly 100-horsepower fan to provide enough differential pressure in the right direction to propel the pod forward.

Granted, the engineering particulars of Musk's concept for Hyperloop aren't exactly the same as the Beach Pneumatic Transit system. But at least from a purely aesthetic perspective, the parallels are indeed profound. Alfred Beach presented his first scale model for a pneumatic pod transit system at the American Institute Fair at New York's 14th Street Armory in 1867. Though little more than a wooden suspended tube and a simple mockup transit pod, the Beach Pneumatic Transit system arguably looked even more like a steampunk Hyperloop in concept form than it did in practice.

Starting directly across from NYC City Hall at the intersection of Warren Street and Broadway, it took just 58 days for Beach's tunneling shields to make mince meat of the subterranean soil around 20 feet or so underground, effectively placed smack-dab in one of the basement levels of the structure above, the Rogers Peet Building. White brick adorning the interior station walls located underneath Warren Street, complete with a bronze statue at the entrance to the tunnel reminiscent of Greek and Roman design cues, all made the station a very pleasant place to wait. The trackside goldfish pond and grand piano must've been a treat as well.

Its tram-like rail path was built with an extremely prominent curve that initially ran east using steam power provided from a boiler and blower room near the terminal towards Broadway. From there, it would hook south down Broadway roughly 300 feet or 90 meters towards the opposite end of Murray Street before returning back to the single station on the route. The total distance covered was about a block and some change. The pod itself was a marvelous piece of engineering in its own right. With plush couches to sit on and lit inside by zirconia lamps, the extra artificial light accented the ornate woodwork inside the pod as it made its transit through the basement of what was then Devlin's Clothing Store.

Though undoubtedly more of a novelty for city folks to gawk at than a functional subway, the resulting fanfare when Beach's Pneumatic Transit line opened on February 26th, 1870, couldn't be denied. Hundreds of thousands flocked to Lower Manhattan to ride a transit system in the making unlike any other in the world. With only one car and one station total, the economy of scale, when applied to an entire multi-line subway system, would've made Alfred E. Beach rich beyond most people's wildest imaginations if it expanded. By all metrics, it looked like that's the direction the Beach Pneumatic Transit system was headed. So the story goes, plans even called for the system to expand past New York Central Railroad Territory on 42nd Street and as far north as the southern tip of Central Park near the 59th Street-Columbus Circle station.

In short, Boss Tweed wanted Beach's proto-hyperloop idea for the New York City Subway thrown in the trash in favor of projects he was invested in. As it turned out, Boss Tweed was personally profiting on every single above-ground passenger train that made its way into Manhattan. He had plans to effectively take the modern paradigm of the Subway and bring it above ground if given his way. With Boss Tweed's increasingly greased palms perpetually interfering with attempts to expand New York's Pneumatic Transit line, a ridership of 400,000 people during its first year at 25 cents a pop (almost $6 in 2024 money) wasn't enough to save the line from archetypal NYC corruption.

Turns out, Boss Tweed was a leading member of NYC's Tammany Hall elite who initially denied Beach's proposal. Suffice it to say, Tweed went full nuclear with rage when he learned he'd been tricked into letting Beach build a "mail tube system" right under his nose that became a rival to his elevated rail ambitions. But believe it or not, it wasn't Tweed who tombstoned the Beach Pneumatic Subway. He wound up (for once in one of these corruption stories) getting what was coming to him after being convicted of stealing New York taxpayer money as a member of the State Senate. He died in Lower Manhattan's Ludlow Street Jail in 1878, but not before a failed escape attempt.

Instead, one of the largest pre-1929 stock market crashes in the history of the New York Stock Exchange meant that by 1873, funding to expand Beach's Pneumatic Transit network, by which time he had the green light to go ahead, had dried up. By the end of the year, the line was completely abandoned, and the building above was lost to fire in 1898, two years after Beach himself died of Pneumonia, aged 69. After the fire, the remains of the tunnel were photographed, with some posing inside the derelict passenger pod before being boarded up and sealed, not to be seen again until 1912.

Well, the answer can only be described as *shrug*. In truth, it's pretty up in the air, with speculation running rampant in online forums like Reddit about what remains. As recently as late March 2023, a YouTuber going by kbnyc traveled to the building built after the 1898 fire and ventured three floors down to its sub-basement to look for clues of Subway's past. Indeed, the plaque in the front lobby of 258 Broadway, now known as City Hall Tower, at the corner of Warren Street commemorates the historic transit system hiding underneath. Today, the basement is full of bicycles used by the tenants who live upstairs, as well as the occasional roughly pug-sized New York mutant super rat.

But as this adventurous YouTuber walks further across the basement floor, a very familiar yet dilapidated set of white bricks with dingy, faded paint appears. It also happens that the bricks are arranged in an equally identifiable curve arrangement. With that in mind, it's at least a safe bet, but not a sure thing, that we're looking at all that remains of New York City's true first underground transit network. On the other end of that wall supposedly sits infrastructure for the local BMT R train between Bay Ridge–95th Street in Brooklyn and looping through Manhattan, usually to Forest Hills–71st Avenue station in Queens.

So far as we can tell, the basement resides on the site of the former station waiting area, where people would descend a flight of stairs to board their pod. Moving to the next room, which has to be propped with a piece of wood, leads to the only staircase in this portion of the sub-basement, after which appears an array of ancient-looking coal furnace piping that might indicate that it's the former location of either the blower or boiler room. In addition, he locates a semi-separate section of the room that might've served as the on-site bathroom.

To think such an unappreciated icon exists a mere stone's throw away from both the current Brooklyn Bridge–City Hall station and the long-abandoned crown jewel of the modern New York Subway, old City Hall Station, makes this part of Lower Manhattan effectively like sacred grounds for fans of metro transit around the world. But speaking of Old City Hall, that's a story for another time; be sure to stay tuned for that.